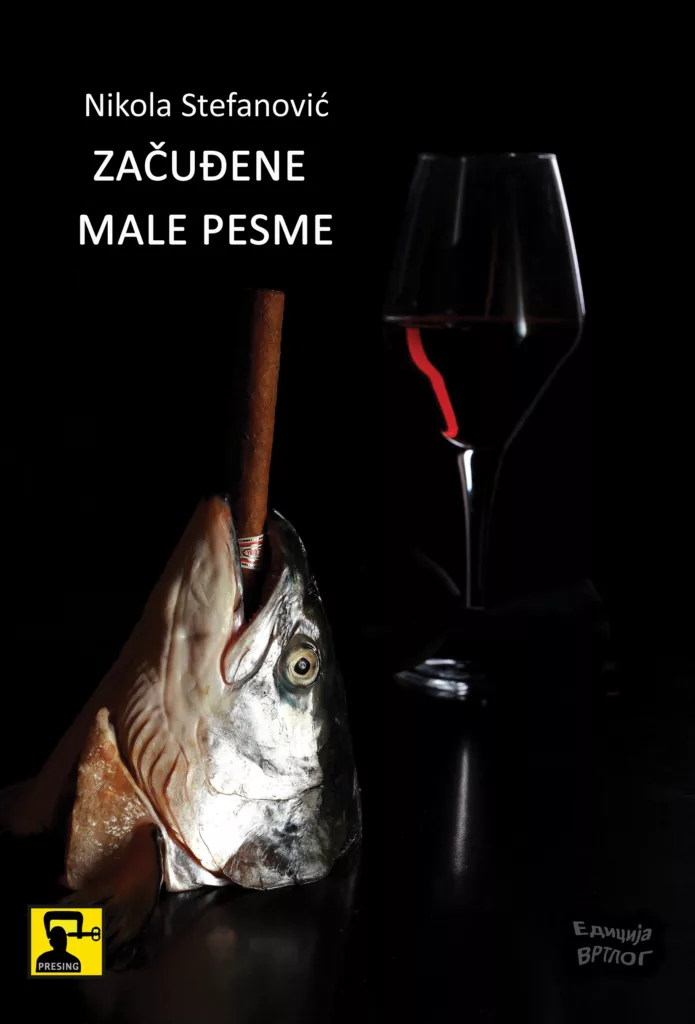

Following his notable poetry collection “Začuđene male pesme” (“Bewildered Little Poems”) (Presing, 2023) and winning first prize for poetry at the “Tragom Nastasijevića” (“Tracing Nastasijević”) contest in Gornji Milanovac (Serbia) that same year, Nikola Stefanović further affirms his presence on the contemporary Serbian literature scene by having his new poems selected for the “Panorama nove sprske poezije 2025” poetry anthology (“Panorama of New Serbian Poetry 2025”), placing him among the fifty most interesting poetic voices in Serbia today. Among the members of the Cultural Club “Prejaka Reč” (meaning: “A Word Too Strong”), Nikola is regarded as the Club’s finest poet (along with other members who have also received awards for poetry, such as Aleksa Bošković, Dušan Milenković, Nemanja Vujičić, Jadranka Milenković, to name a few). His poetry, filled with evocative poetic imagery, often turns to memories from earlier times, from childhood, not expressing nostalgia as the primary emotion, but using these images to contemplate and present the more complex challenges of human existence. The tremulousness, ostensible naivety, and intentional simplicity of these poems will lead connoisseurs of poetry along associative pathways all the way to the suggestiveness of haiku poetry, toward a re-examination of ancient epic tradition and back again, passing through some of the most significant names of Serbian verse-making, right to the very center of contemporary poetic currents in our language.

Introductory words by Jadranka Milenković. The introduction and the poems translated by Igor Vesović.

A TOOTHPICK THAT THINKS

As though in consciousness,

in a big white plate,

I’m chasing an olive

with a toothpick,

for hours.

Whatever I think

it’s round

whatever I think

an olive I think

with words of sense and meaning

and I get tired.

Yet the bed I’ve made,

soft my bedside,

near the power meter.

And I listen to it buzz

as everything buzzes

inside and out

buzzes incessantly,

through the atoms — a void.

My name I hear, too.

A calling, outside, from nowhere.

How come the field knows my name?

I place rags over the window, I turn up the telly

I turn on the shower head…

No use, it calls and calls, yelling and yelling.

The world is a hollow snail-shell

calling me to enter

and carry it with my body until the first dew.

SING ME SOMETHING ELSE

Wrath, O Goddess, sing me not,

’tis plenty.

Sing me morning that doth eternity on earth mirror

and sing me how on earth awaken the men meagre.

From a certain distance resembling pups,

collecting the shards of warmth in a white promise rowling

reluctantly leaving the bedding’s embrace

as if fast to heaven’s gates they’re holding.

Sing me, O Goddess, how somnolence to brother still turns a murderous foe,

how men delay the alarm as though shutting a door.

And unwillingly so, at the eleventh hour, as by another’s faith,

they rise into a world built by their measure

so in a crowd to fade.

HIDE AND SEEK

Fear found me.

And now I jump out of the hideout,

hurrying to home base to yell “Free!”

If it gets there first I’ll have to be “it”,

to shut my eyes and count

and then once again myself and others

around me to seek.

Yet the street extends

and the fear is quicker by a beat of its steps,

I won’t yell,

I run.

My lips hold the age-old sentence

the magical:

“Olly olly oxen free”

Not for me,

O God, not for me,

for us all.

Yet I trample and fall,

not only fall,

as a genie from the lamp

into a stone I crawl

and slowly I roll,

too slow, without hope.

The golden sentence

slips from my lips.

It rolls me — the stone —

rolls me faster than I’ve ever lived before.

The street echoes:

“Olly olly oxen free.”

Everything falls to its measure

the fear is a flood gone dry,

the stone is but a memory upon my heart.

WALL

The road leads through a wall.

Then again through a wall.

And then through a wall, through a wall, through a wall.

After that the light is soft,

yet after so many blows

it, too, feels like a wall.

ANGEL

When we were small, there was snow.

And we, as children, made angels in the snow.

In snow which,

as if by a ritual rule,

was not to be stepped on.

We made voids in the whiteness,

we took from it guilelessly

without thinking of misuse,

we — the children.

Only now do I understand,

that void of shape, a respite of weight, a space made free,

that gentle yielding,

was in fact an Angel following us, since we were small,

keeping our world safe

from winter which, without snow, would

grow within.

Poems translated by Igor Vesović.